CHARLIE HAINES & CAMP HILL Gallery

Charlie Haines and Camp Hill

With Flower Show behind us and the clocks springing us ahead, we thought this month we’d turn our attentions to the story of Camp Hill and its first owner, Charlie Haines, as Haines was an avid planter of unique and interesting trees.

From what we know, Camp Hill was likely a pa site as, for many years, Charlie found a large number of artifacts there (often, according to his niece, Rosie Grant, dug up by his pigs). Haines took the region’s history very seriously and the Otago Museum’s collection contains a significant number of pieces of greenstone and carved moa bone and flax pieces all found by Haines in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries. You can see in this month’s photos five pieces from the Haines collection that they’ve photographed for us, including a fantastic pair of paraerae – flax sandals used for long distance walking -- as well as some greenstone pieces that date back to moa butchering days.

Charlie came to Camp Hill in 1877, just as the first sections were being prised away from John Butement’s North Station for smaller farms at Mid Rivers, the Priory, the Hillocks, and at the foot of Mt. Earnslaw. Charlie was one of eight siblings who had come out from Ireland with their parents and had begun goldmining in the Shotover. Though they made a series of attempts at purchasing land at the Head of the Lake, only Charlie and his sister Eliza (or Lottie, as her neighbour Sara Cockburn called her) were successful. Eliza took land that today is Earnslaw Station, and she built a small hut there that was technically her residence, while Charlie, her bachelor brother, took up Camp Hill where he pursued a wide range of interests.

A visitor in 1887 described the dry humour with which Charlie approached his location. “On the hither side a Mr. Haynes (sic), an Irish storekeeper, has recently purchased a property; and, with Hibernian humour, has christened it Purgatory, because, as he says," you must pass through Purgatory before you reach Paradise."

Sara Cockburn described life at her brothers George and David’s farm in the early days. (And yes, Cockburn’s bush is named for the Cockburns, if you’re wondering…)

“Our nearest neighbours were Charlie Haines and his sister Lottie, of Camp Hill Farm. Charlie was a collector of Maori relics. Adzes found by him in old Maori camps at the Head of the Lake are now in the Otago Museum. He was a unique character, ‘agin the government’ on most issues, but a lover of birds, and trees and flowers and given to generous hospitality. Some of his neighbours thought he wasted his time reading papers and books, and wandering over the hills pursuing his ‘cranky’ hobbies.”

She gives us a glimpse into the conversation taking place at Charlie Haines’:

“While life at the Head was free and open, it was very lonely for a girl of sixteen. I read a great deal, concentrating on the Bible and George’s books on astronomy, and I suppose my mental faculties were sharpened by listening to discussions, on the long winter evenings around the blazing log fire, between George and Charlie Haines on the theories of Charles Darwin and the ‘free thought’ of Robert Ingersoll.”

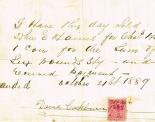

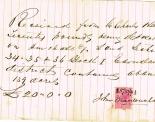

Though she would leave, her brother George stayed on at the Head of the Lake and played a role in much of early community life. You can see among this month’s photos a receipt he signed for the sale of a branded cow between Eliza and Charlie.

Though Charlie Haines was a bachelor, another of his sisters, Ellen, also married a local sawmiller, Bill Grant, whose daughter Rosie would live out a very long life spanning nearly the whole of the 20th Century at the Head of the Lake.

Charlie was generous in that he provided the community with a place to hold the school picnics, even though he didn’t have children of his own. During the wars when he refused to support the English cause (he was Irish…and his obituary makes mention of his politics) some parents didn’t want to attend the school picnic and it became something of a political issue. He also wasn’t terribly keen on the road from the 1922 Rees Valley bridge crossing his section so he made things quite tricky for Council. The shape of the roads crossing the Rees Valley today may have a little to do with his unwillingness to have them cross his land.

Charlie died on 11 January 1945 and his obituary in the Lake Wakatip Mail includes a description written by “A Miner” from Glenorchy. The Head of the Lake has always been home to people who have pursued their own interests and given to the community in their own ways. Here’s our Miner’s tribute…the uniqueness of Charlie Haines’ character and his love for the land could describe many of GY’s residents today, too.

At the age of 86, Mr Charles Haines of Glenorchy, died on, January 11. He disregarded many orthodox practices, even in diet, but 86 is a good innings. Leaving his father’s store in Queenstown when he was only a youth, he took up a section at Rees Valley, Glenorchy. He built his house at Camp Hill, near the foot of Mount Earnslaw, and planted fruit trees, timber and ornamental trees in profuse manner in many corners of his farm. In its heyday and his own, there were a pond, a water wheel, clover paddocks, and all the farm animals, even to fish, in the stream near the house.

In later years he minimised the work, devoting himself to his flowers, his books, and his collections. His searches for Maori relics led him to explore the country away to the West Coast, and a number of adzes from his collection have been presented to the Otago Museum.

He lived an aesthetic, financially comfortable life, to all appearances unworried domestically. He remained single, and was, in fact, a lone monk, with no retreat to, or affiliation with, religion. Abstemious to a degree, a non-smoker, non-gambler, a non-philanderer, he regarded clothing as a means to an end and not as an object in itself. People said that he wasted money in buying books and papers, and that he wasted time in reading them, and in wandering over the hills pursuing some of his hobbies.

Mr Haines was generous in his hospitality. All visitors were welcome, and time and food were given in delightful disregard of both. And there was talk, mostly his talk. A full mind must overflow in talk; the pen is a poor substitute. He was not a strong, silent man, he was a slim, talkative one, and few men ever talked less to suit their audiences. Women whose main thoughts wore on gossip and diseases were bored with his discourses on politics. But sometimes it did suit. A Sydney paper about 30 years ago contained a paragraph stating that Sydney ladies would have to brush up their reading, as a traveller in Maoriland met behind the hills of Glenorchy a farmer who discoursed freely on the merits of Turgency and Dostoevski. This would be true in the case of many tourists to the Head of Lake Wakatipu, who made it a point of calling on Charlie Haines at Camp Hill.

He also had his hobby horses; he dug up information from many remote quarters to show that British Imperialism was generally wicked aggression. Minority mindedness would not fully explain him, but if there was any case in which the few were against the many, he would enthusiastically state the case for the few.

Throwing bricks at the people’s idols in politics, literature, or religion, does not tend to gather together many friends, but it takes many people out of mental ruts and makes them aware of the clashes that exist in the world of thought. Haines was never a ‘‘yes” man. He could ably defend his line of thought, but had never an occasion to defend his line of conduct. He did his best not to hide his talents under a bushel; he preserved the native bush on his land; he planted flowers and trees; he gathered Maori curios, and he made it actually more difficult for those people who would classify New Zealanders in groups. You could not write Charles Haines down under some heading and make a big tally at the bottom. Another of Central Otago’s unique characters has now left the stage.

These days the tradition of caring for the land at Camp Hill has been in Rob’s good hands and thousands of native trees have been planted. One would imagine, Charlie Haines would be quite pleased and this month we’re happy to celebrate Charlie Haines’s legacy.